Bacteriophages may be able to help fight tuberculosis, an infectious disease that kills more than a million people each year. In an international collaboration with South African and American research institutes, Radboud university medical center is investigating how bacteriophages can be used in the fight against tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The disease kills more than a million people every year, particularly in Africa. It is a condition that is difficult to treat: the regular antibiotic treatment for tuberculosis lasts six months, and there is also a multi-resistant tuberculosis variant, which does not respond to the most commonly used types of antibiotics. Treatment can then take more than a year.

Nijmegen-based Radboud university medical center is now joining forces with research institute TASK (South Africa), the University of Pittsburgh and the Seattle Children's Research Institute (both from the US) in the Phages4TB project, for innovative research into new treatments for tuberculosis. To this end, TASK receives a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, part of which will be made available for research within the Radboudumc. In this study, the researchers at these institutes make use of the possibilities of mycobacteriophages, viruses that are specifically targeted against mycobacteria such as the tuberculosis bacterium.

Difference between antibiotics and bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (or phages) are viruses that can infect and kill bacteria. Treatment with bacteriophages was widely used before antibiotics were available. An important distinction between the two treatments is that antibiotics target different bacterial species at the same time, while bacteriophages are only active against one particular strain of bacteria. Bacteriophages can be a solution if antibiotics do not work, but a disadvantage is that they cannot be used quickly against infections. Researchers first have to track down the pathogenic bacterium, only then can they look for matching phages. Antibiotics are easier to use due to their broader activity, which means that phages received less attention for a long time. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in phage therapy, fueled by increasing antibiotic resistance worldwide.

New tests in the lab

Physician-microbiologist Jakko van Ingen leads the Nijmegen branch of the research and is positive about the opportunities for bacteriophages in the treatment of TB: 'The disadvantage of phage therapy is that in many infections you have to look for the right phages that catch on to the pathogenic bacterium. That doesn't always work. The tuberculosis bacterium, however, has little variation, all species resemble each other. That's why we think we have a combination of phages that we can use to treat most TB patients.'

Preparations for this have been made at the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers there developed a phage combination that responded in the laboratory to the main variants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. From here, the partnership continues. Project leader and infectiologist Saskia Janssen, affiliated with TASK in Cape Town and at Radboud university medical center, explains: 'Our main objective is the further development of this phage combination. We still do this in the lab and through animal experiments, the latter being done in Seattle. In addition, we are preparing for the first clinical studies in humans.'

First Dutch study of tuberculosis with bacteriophages

Never before has a Dutch knowledge institute conducted research into new treatments with bacteriophages aimed at tuberculosis. At Radboud university medical center, Van Ingen will conduct specific research into the activity of bacteriophages in the different conditions in which the tuberculosis bacterium can find itself. The TB bacteria can hide in immune cells and go into hibernation. The research aims to find out whether bacteriophages are still lethal to the bacterium. His goal is clear: 'We hope to develop an alternative to standard TB treatments, which often take a long time, have relatively many side effects and are sometimes difficult to work. Ultimately, we want TB to stop threatening global public health.'

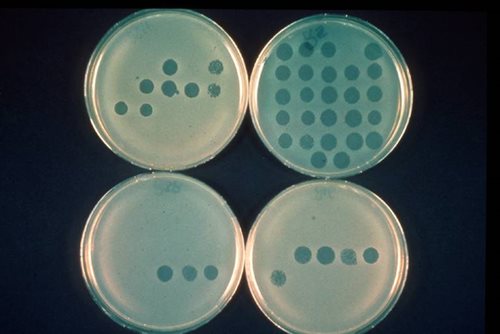

In this picture: the dark circles are spots where the bacteriophages attacked the tuberculosis bacterium.

-

Want to know more about these subjects? Click on the buttons below for more news.

More information

Pauline Dekhuijzen

wetenschaps- en persvoorlichter